- Name: Catherine O'Donnell

- Age: 22 in 1889

- Emigrated: From Ireland to Boston in 1888

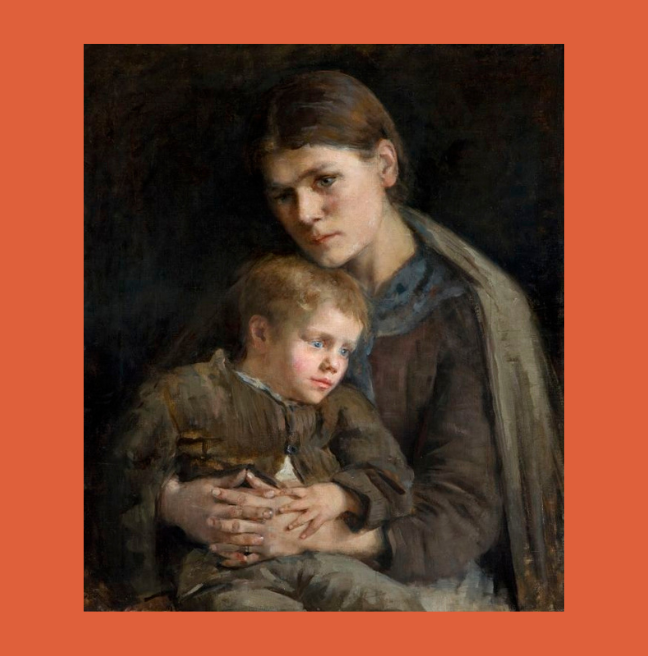

Our relationships were often complicated. Some of us experienced difficult domestic lives, others struggled with childcare responsibilities or had to cope with the shame of giving birth outside marriage.

The girl acted in a fit of desperation.

Boston Globe

23 May 1889

Back in Ireland, my father’s a well-respected man. He has two hundred acres to his name. When he’s gone, the land will go to our Edward—for John’s already in the priesthood and Patrick’s settled in Providence. He’ll take me in when my sentence is finished. I could change my name; try to start again. If he doesn’t take me, I’ve no place on this earth to go. It wouldn’t have been any different if I’d stayed at home. They’d have taken the baby off me; maybe even packed me off to the Workhouse. My father doesn’t do well with shame and I could never tell him his weasly old bookkeeper was responsible. I booked my passage to Boston before I started showing. I thought he’d never have to know.

In the beginning I did alright. There was money coming from home. That stopped when daddy heard about my state. After the baby came, I got work in the mill. I boarded the child out with a Mrs Lyman. It was filthy and she already had a rake of babies but what choice had I? Soon I couldn’t even afford two dollars fifty for her board. I went all over Boston looking for a place for the child. The Massachusetts Infant Asylum. The Almshouse. The Boston Female Asylum. As soon as they heard I was unmarried, they shut the door firmly in my face.

The next days are a blur. I wandered around for two days in the lashing rain. The pair of us were drenched to the skin. By evening of the second day, the little mite was dead in my arms. I was so exhausted I didn’t know what to do. A stranger took me to the depot so they could bury her. The next day I was working—I had to, or I wouldn’t eat—when the police appeared and arrested me. They said I’d left my baby to drown in the tide over on Swett Street. I remember it different, but at least they were kind. Nobody had been kind to me in such a long time. The Judge did everything he could to help. I’ll only be in for a year.

They’re a lowdown sort of breed in prison: thieves and whores, common drunks. A world away from the girls I spent years with in the convent. I wonder if they’d think me a monster, accused of having killed my own child. I’m many things but I’m not a monster. I loved that baby. I did everything I could for her. Still, when I think about how things turned out, I’m so ashamed. Ashamed and angry too, for the good-living folks of America are no different from the ones at home. They’ll talk about their charity but when you turn up on their doorstep looking help, they’ll slam the door in your face.